By Val Bogart

Dissection of a human corpse, outside of an official autopsy, was looked upon as a disgrace in the 19th century. Every person was afforded the right to a decent burial, and the right to remain interred once buried. Medical colleges at the time were only permitted to use unclaimed bodies for their anatomy classes, but since dissection was a requirement for graduation and there was a shortage of unclaimed bodies, many had to procure them illegally. It has been estimated that over 5,000 bodies were snatched from Ohio graves in the 1800’s.

The method of “resurrection” as it was known, was so refined that most people were never even aware when it happened. Grave robbers targeted freshly dug graves so the disrupted plot wouldn’t attract attention. Women were hired to attend funerals posed as grieving loved ones, so they could get the inside scoop on burials. Meanwhile, actual grieving loved ones had no idea that they were visiting grave sites where only empty coffins remained. Laws were repeatedly passed to impose increasingly stricter guidelines on the handling of corpses, none of which deterred the practice of grave robbery. The poor and indigent proved to be easy targets.

Sometime in the 1830’s, a respectable woman from Marietta, Ohio, who had become deranged and then subsequently ill, died in the State Lunatic Asylum. The roads were especially muddy at the time, causing some travel delays, so instead of waiting for her family to arrive, it was decided that she would be buried in a Potter’s field. When her son came to claim her body, he went to the cemetery only to find that her grave was empty. Two other graves in the same cemetery had also been disturbed, and suspicion pointed to the nearby Worthington Medical College.

Worthington was one of the first accredited medical colleges in the country to practice “eclectic” medicine, which rejected common medical practices in favor of more natural and therapeutic remedies. The son had it on good authority that persons associated with the school were digging up bodies not only for anatomical study purposes, but for trade. He obtained a search warrant for the medical building and what he found was horrifying: hidden beneath a trap door situated in the center of the building was the head of his beloved mother.

The pinnacle of outrage played out for Worthington in the notorious “Resurrection Riot” of 1839. When news of the increasing number of empty graves had spread far enough, an angry mob assembled and demanded a search of the medical building. Faculty and students at Worthington responded by arming themselves with firearms. Battle was about to ensue when someone caved and handed over the keys to the building. Worthington offered up a truce – they would agree to cease and desist, so long as they could retain their removable property. The offer was accepted, and the Worthington Reformed Medical College closed its doors, only to reopen in Cincinnati under a new name: the Cincinnati Medical Institute, which would soon merge to form the Eclectic Medical Institute of Cincinnati.

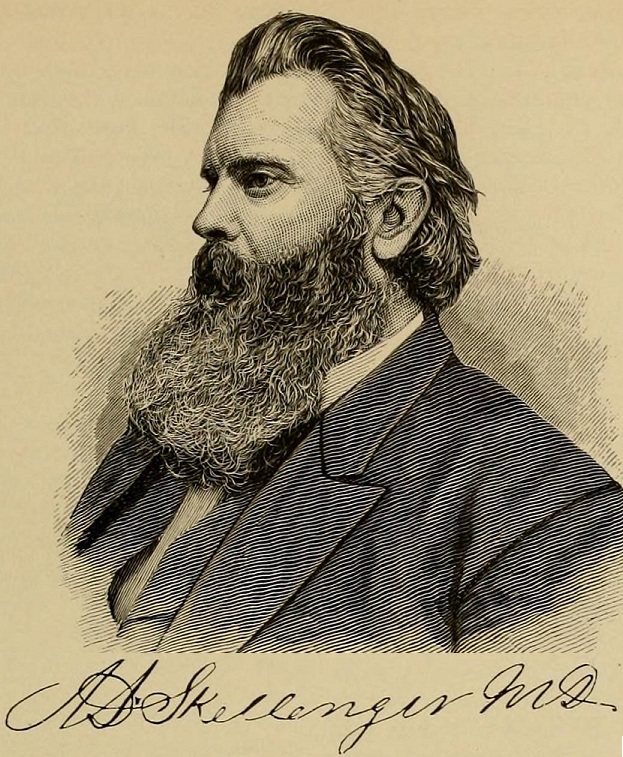

Anson Deering Skellenger was a notable graduate of the Cincinnati Medical Institute in 1850. After continuing his studies in Cleveland, he finally settled in New London in June of 1853, where he would live until his death in 1895. Dr. Skellenger became a big deal in New London. He ran a hotel, served as Mayor and Probate Judge, founded the New London Library Association, and was a well-respected physician and surgeon, regarded by the community as generous and friendly. Skellenger was a member of the National Eclectic Medical Association and contributed to numerous medical journals.

After a cultural analysis of census records spanning from 1880 to 1940, it can reasonably be inferred that the person residing at 118 E. Main Street in New London in 1881 (where Hallie’s bones were found) was none other than Dr. Skellenger.

Skellenger frequently attended lectures at the University of Louisville, Kentucky in the late 1870’s. The trip from New London to Louisville was just a little over 300 miles, and the route he would have taken went straight through Clinton County, where Hallie Armstrong lived, died, and was buried. Skellenger was surely aware of the grave-robbing activity in the area, if not himself a cohort. He could have easily picked up her body on his way to or from a lecture. It could have also been procured by someone for use at the medical college, and Anson may have simply collected her bones to take home for further study. It doesn’t seem likely that Hallie’s parents would go to the trouble of purchasing a burial plot and having her body interred if they were just planning to donate it to medical science.

If Clinton County was along a well-traveled route, then other bodies from the same cemetery where Hallie was buried may have also been snatched. It’s also possible that there were some sketchy undertakers in Clinton County that were publicly burying empty caskets, but privately selling corpses to the medical college.

After much consideration, the Porchlight Project believes this is the most likely solution to the puzzle of how Hallie Armstrong’s remains ended up in a barn in New London, Ohio. We are now taking steps to return her remains to the cemetery plot from where they were stolen, some 140 years ago.